تخبرنا منظمة الصحة العالمية عن نجاح الهند في القضاء على شلل الأطفال في العام ٢٠١٢ بخلاف دول مثل باكستان وأفغانستان ونيجيريا.

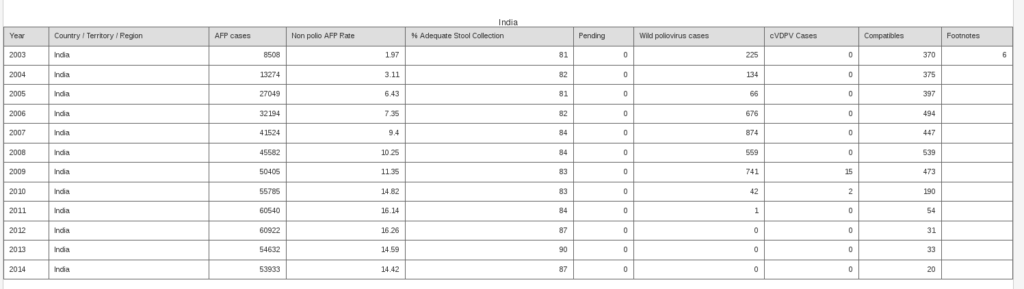

لكن حين الاطلاع على احصائيات منظمة الصحة العالمية نفسها من العام ٢٠٠٣ إلى ٢٠١٤ (١) نخرج بقراءات مغايرة:

- في ٢٠٠٣ كانت أعداد الشلل الرخو الحاد acute flaccid paralysis (جميع إصابات شلل بدون تعريف المُسبب) ما يقارب ٨ آلاف حالة سجلت منها ٢٢٥ حالة (مؤكدة) تعود للفيروس البري لشلل الأطفال والتي تستهدف خفضها حملات التطعيم المتكررة باللقاح الفموي.

- بعد 9 سنوات من حملات التطعيم المتكررة والجماعية، احتفلت الهند بتحقيق صفر حالات شلل الأطفال من النوع البري وذلك في العام ٢٠١٢ لكن مع فارق تسجيل رقم قياسي لمعدل إصابات الشلل الرخو الحاد ولأعداده.

- على مدى سنوات حملات التطعيم الجماعية المتكررة نلاحظ الارتفاع المتزايد في عدد حالات الشلل الرخو الحاد في الهند إلى أن سجلت ٦٠ ألف حالة في العام ٢٠١٢، بالمقارنة ب ٥ آلاف حالة في ٢٠٠٣ عند بدء الحملات. وكذلك ارتفاع معدل حالات الشلل الرخو الحاد من ٢٠٠٣ إلى ٢٠١٢.

- إن رجعنا للمقارنة باحصائيات ما يسمى الفشل الباكستاني في القضاء على شلل الأطفال فسنجد تسجيل ٥٠ حالة شلل أطفال (فيروس بري) في ٢٠١٢ وهو أقل عددا و يشكل نصف معدل حالات شلل الأطفال الهندي.

- المعدل الباكستاني AFP ٨ لكل ١٠٠ ألف حالة في حين أن المعدل الهندي هو الضعف تقريبا ١٦ لكل ١٠٠ ألف حالة. ومجمل أعداد شلل رخو حاد في باكستان ٥ آلاف، في حين أنها في الهند تتجاوز ٦٠ ألف سنويا في ذات العام الذي أعلنت فيه الهند خلوها من شلل الأطفال.

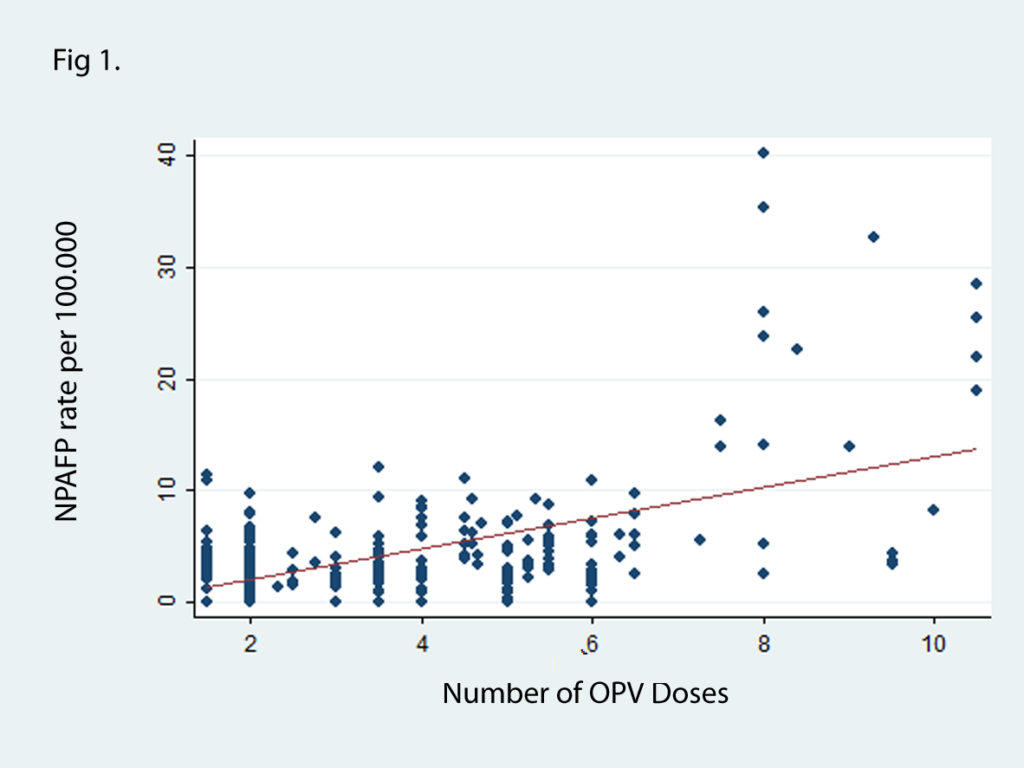

- خلصت دراسة عن التجرية الهندية -نشرت عام ٢٠١٤ – إلى تواجد رابط إيجابي بين ارتفاع أعداد حالات الشلل الرخو الحاد و عدد جرعات لقاح شلل الأطفال الفموي المعطاة ضمن حملات التطعيم الجماعية في الهند، ترابطا لا يمكن تجاهله ومتعلق بعدد الحملات والمقاطعات التي أجريت فيها ربطا مباشرا.

يحق لنا التساؤل: هل يعدّ هذا النجاح الهندي هو المثال الذي على باكستان أن تتبعه؟ وهل هذا النجاح غير المرتبط بتحسن صحة الطفل الهندي يعدّ مبررا لأن يًرسل الآباء الباكستانيين الرافضين إلى السجون وأن تجرى حملات التطعيم تحت تهديد السلاح وهو ما يعد مخالفة للشرع والقانون والأخلاق؟

بالطبع لا.

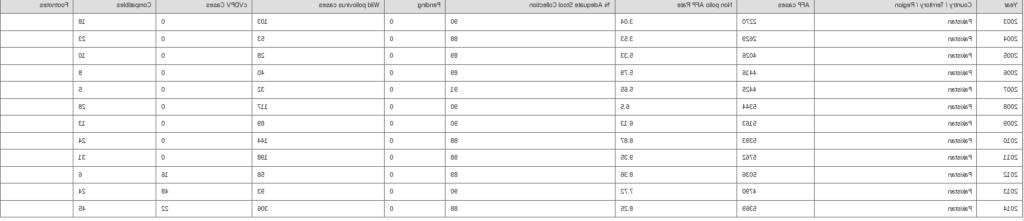

احصائيات شلل الأطفال في باكستان خلال أعوام ٢٠٠٣-٢٠١٤

من الدراسة (2)

1. Our results indicate that the incidence of non-polio AFP was strongly associated with the number of OPV doses delivered to the area. We also observed a dose response relation with cumulative doses over the years, which further strengthens the hypothetical relationship between polio vaccine and non-polio paralysis.

The fall in the non polio paralysis in Bihar and UP for the first time in 2012, with a decrease in the number of OPV doses delivered, is further corroborative evidence of a causative association between OPV doses and the NPAFP rate.

2. Follow-up of these cases of non-polio AFP is not done routinely. However a fifth of these cases of non-polio AFP in the state of Uttar Pradesh were followed-up after 60 days, in 2005. 35.2% were found to have residual paralysis and 8.5% had died (total residual paralysis or death 43.7%). There is thus an urgency to identify the reasons for the surge in non-polio paralysis numbers and take corrective measures immediately.

3. It is possible that factors that result in higher polio incidence in these states, like overcrowding and poor sanitation also promote spread of entero-pathogens which cause non polio paralysis. However poor sanitation by itself cannot explain why the incidence of non-polio paralysis should increase year after year in the same area, in proportion to doses of polio vaccine administered here.

4. Some have attributed this increase in non polio paralysis to good surveillance. A surveillance programme no matter how good, can only record every case of AFP, but it cannot exaggerate the numbers or explain the 25 to 35 fold increase in the non-polio AFP rate, as seen in the state of Bihar and UP (2010). In fact it is the states with the best health indicators and therefore presumably the best surveillance that have some of the lowest non-polio paralysis rates

5. The NPAFP may be considered as collateral damage in the effort to eradicate polio. It was hoped that after polio eradication the use of oral polio vaccine could be stopped and it could result in the reduction of NPAFP. However it is realised that this is unlikely to happen in the near future given the economic and logistical hurdles in switching to IPV

Therefore, our study would like to urge the experts to optimise the dosing schedule of OPV so as to prevent an inadvertent increase in non –polio paralysis in India.

The fall in the non polio paralysis in Bihar and UP for the first time in 2012, with a decrease in the number of OPV doses delivered, is further corroborative evidence of a causative association between OPV doses and the NPAFP rate.

2. Follow-up of these cases of non-polio AFP is not done routinely. However a fifth of these cases of non-polio AFP in the state of Uttar Pradesh were followed-up after 60 days, in 2005. 35.2% were found to have residual paralysis and 8.5% had died (total residual paralysis or death 43.7%). There is thus an urgency to identify the reasons for the surge in non-polio paralysis numbers and take corrective measures immediately.

3. It is possible that factors that result in higher polio incidence in these states, like overcrowding and poor sanitation also promote spread of entero-pathogens which cause non polio paralysis. However poor sanitation by itself cannot explain why the incidence of non-polio paralysis should increase year after year in the same area, in proportion to doses of polio vaccine administered here.

4. Some have attributed this increase in non polio paralysis to good surveillance. A surveillance programme no matter how good, can only record every case of AFP, but it cannot exaggerate the numbers or explain the 25 to 35 fold increase in the non-polio AFP rate, as seen in the state of Bihar and UP (2010). In fact it is the states with the best health indicators and therefore presumably the best surveillance that have some of the lowest non-polio paralysis rates

5. The NPAFP may be considered as collateral damage in the effort to eradicate polio. It was hoped that after polio eradication the use of oral polio vaccine could be stopped and it could result in the reduction of NPAFP. However it is realised that this is unlikely to happen in the near future given the economic and logistical hurdles in switching to IPV

Therefore, our study would like to urge the experts to optimise the dosing schedule of OPV so as to prevent an inadvertent increase in non –polio paralysis in India.